The proof is in the product? Two new studies affirm community monitoring’s potential to deliver better public infrastructure

Imagine taking a different route home and spotting a new construction going up in your neighbourhood. Perhaps you notice it’s a new health clinic, or a school building, something that might improve your life. Sometime later you pass by again – only to find an abandoned building site, with walls already crumbling and piles of taxpayer-funded materials left to rust.

This scenario is all too common in many communities where Integrity Action works. Stretched beyond their capacity, local governments can lack the time, resources, or inclination to properly oversee public construction projects. But what if ordinary residents could act as monitors, tracking progress and flagging issues? Would such community monitoring lead to better infrastructure?

Two of our recent studies from Kenya and Ghana suggest that it just might.

Don’t want to just sit there reading about them? Try this interactive quiz instead!

The first is from Kwale County, Kenya, where Integrity Action and KYGC have been supporting community monitoring since 2017. Last year we published a data story that looked at 168 projects that had been monitored by local citizens, exploring some of the 2000+ problems that had been identified and how 80% of these had been resolved. In our new study, we broaden our horizons beyond just these projects.

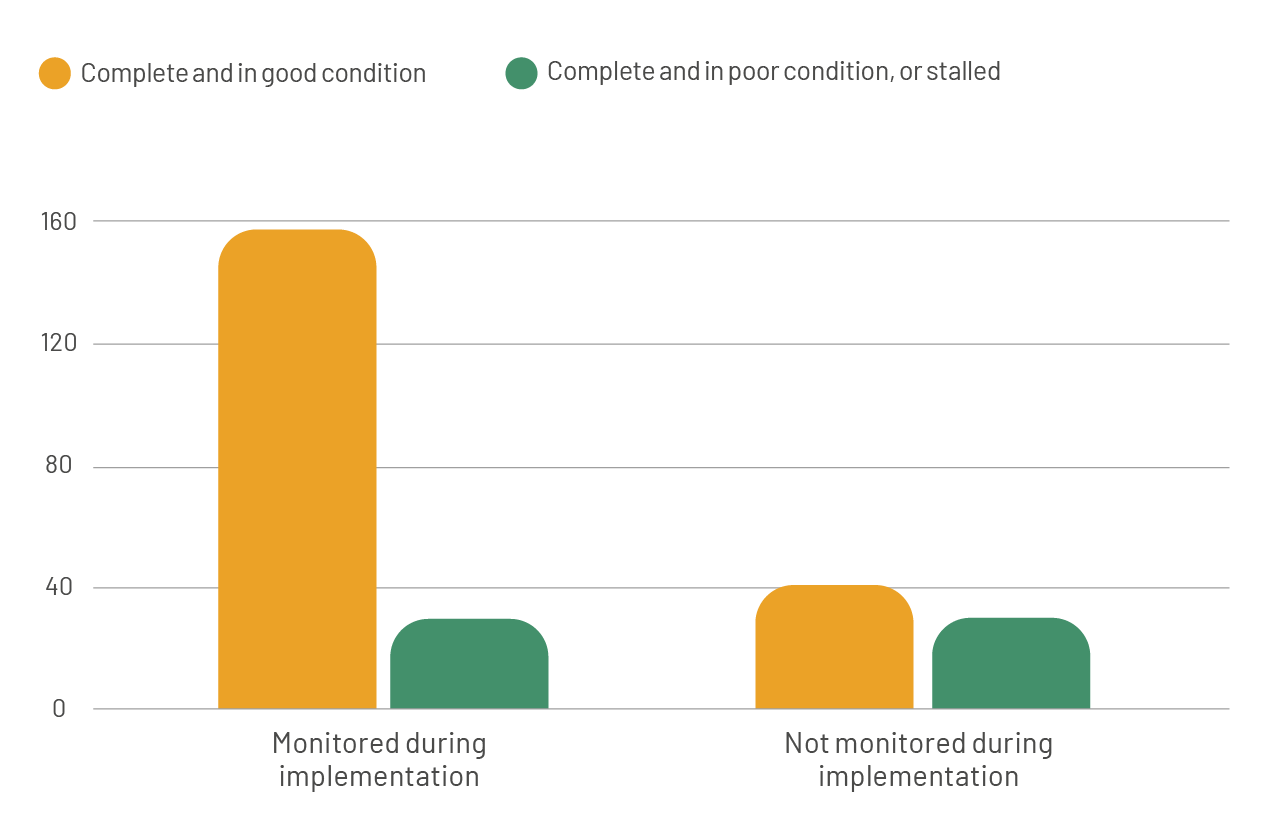

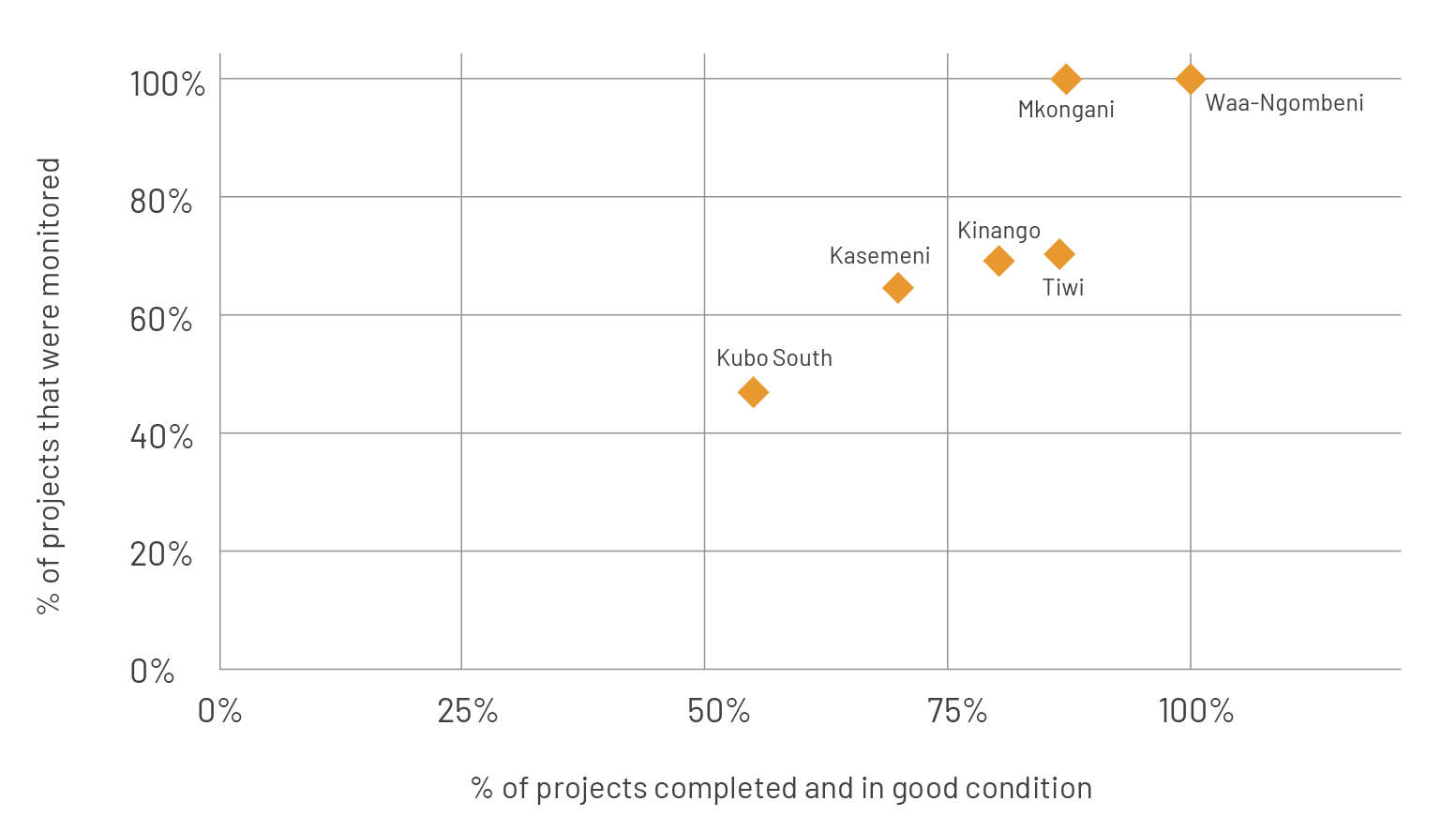

This new study saw volunteer researchers visiting 283 recent public infrastructure projects from across the county, and reporting on their condition. The list included more than 100 early child development and education centres, alongside health dispensaries, water kiosks, maternity wings, and more. About three-quarters had been monitored during implementation, with the others visited for comparison. Statistical analysis then shows that the constructions that were monitored are significantly more likely to have been found in good shape – and especially when community monitors (from the VOICE programme) had been involved.

Of course, we know this doesn’t prove it was monitoring that caused the difference. Importantly, the distribution of monitored projects varied over the six wards covered by the study. Again, wards with a high proportion of monitored projects had a higher proportion of projects in good condition – but is this because the presence of community monitors improved the work done? Or because the same local officials who are more open to community monitoring are also those who already manage projects better? We need to know more to say for sure.

The second study we’ve just published is the result of more than two years’ of research by INTRAC and the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science & Technology (KNUST). This research – titled “Does citizen monitoring save public money?” – explores the different ways in which community monitoring can improve the quality of infrastructure projects, as well as assessing the monetary savings that this leads to. The monitors in question were part of the Monitoring for Financial Savings initiative, implemented by Integrity Action and SEND Ghana since 2021.

At Integrity Action, we believe that involving citizens in project oversight leads to goods and services that better meet their needs – you can read about this in our previous evaluations, as well as in the Kenya data above. That means it’s the right thing to do. However, we believe it can also be the smart thing to do, providing a win-win for governments and others who fund and deliver projects by ensuring they get value for money rather than the false economies of products that don’t last. Putting a monetary value on these long-term savings is something that hasn’t been done before – at least, not as far as we know! – and would be of benefit all sorts of actors across the sector.

Unfortunately, the small sample size, limited access to data, and Ghana’s surging economic crisis meant that the quantitative element of this study was inconclusive. We still believe that the better quality of infrastructure associated with community monitoring saves local governments money in the long run, but we still don’t have the figures to show this.

What we do have is increased insight into three of the ways in which community monitoring adds value.

First, community monitors add value through early detection of problems. Living nearby to the projects, monitors can spot flaws missed by official inspections that may be infrequent or rushed; for example, issues with the original design (such as lack of accessibility), deviations from the agreed specifications, and inadequate allocation of resources. Identifying these problems early means that they can be resolved before they become too expensive.

|

“Because of our frequent visits to the project site [a classroom], we detected some problems at the early stage of the project. When the project started, we realised that the blocks the contractor was going to use for the foundation of the building were not of good quality… So, we alerted the contractor and the necessary changes were made [and] instead of using inferior blocks for the foundation, our monitoring made him use quality ones.” |

Second, community surveillance enhances transparency and incentivises adherence to proper processes. Monitor reports compel contractors to share information and address community concerns. In Ghana, their presence encouraged accountability from officials wary of public criticism. Knowing that projects are being watched is a powerful deterrent to dubious cost-cutting practices such as use of inferior materials.

|

“The contractor nearly reduced the amount of cement used for the lintel if it weren't for our diligent monitoring work. Our presence and scrutiny prevented the contractor from compromising the structural integrity of the building by cutting corners. By ensuring that the appropriate amount of cement was used, we have safeguarded the long-term durability and safety of the infrastructure.” |

Finally, community monitors encourage wider engagement and ownership. Conversations with local residents in Ghana highlighted that the information shared by monitors, and the opportunities for input that monitors had created, had increased demand for public participation. This became a “ripple effect”, with communities more invested in the development of their neighbourhoods and paying more attention to other local initiatives and programmes.

|

“The impact of citizen monitors in our community has been truly remarkable. They provide us with regular updates on the progress of the projects, ensuring that everyone is well-informed and aware of what is happening. Thanks to their work, any issues or concerns related to the projects that are observed by any member of this community are quickly reported to them, the Assemblyman, or even the local authorities. Their presence has motivated all of us to take a keen interest in the development of our community” |

These insights align with Integrity Action’s experience supporting community monitors in countries around the world, and with our previous research into how problems get solved. Taken together, and despite their limitations, these studies affirm the potential for citizen-centred accountability to strengthen public infrastructure. From prompting corrective action to deterring corruption, and even reducing instances of vandalism and theft, community monitoring offers value to those who wish to spend taxes wisely.

Of course, what we also know is that monitors are not by themselves a silver bullet. Their success relies on authorities willing to collaborate and able to respond to concerns. When officials in Ghana acted on problems raised by monitors, tangible improvements followed – but without this, citizens cannot single-handedly ensure perfect projects.

Where citizens participate in oversight, they share responsibility for successful project delivery. Next time you pass by that new building, maybe ask yourself who is looking after it and ensuring it gets done properly. Development actors are also responsible – for advancing solutions centring community oversight to complement traditional governance channels. And we must build on the valuable methodological lessons learned from these studies, revisiting the question of monetary savings through further research and continuing to strengthen the case for citizen-centred accountability.

--

The Kenya study is available here, and the Ghana one here. You can also explore their findings further in this interactive quiz. Finally, watch both studies being discussed by an expert group of panellists at the 2023 Open Government Partnership summit here, with thanks to all speakers: Paul Maassen (OGP), Aidan Eyakuze (Twaweza), Albert Arhin (KNUST), Elsheber Oketch (KYGC), Mumuni Mohammed (SEND Ghana), Courtney Tolmie (Results for Development), and Linnea Mills (GPSA).

If you’re interested in the question of monetary savings, know of any existing evidence, or want to talk about pitfalls and potentials of any particular methodology then email daniel.burwood@integrityaction.org