Social inclusion in social accountability: combining online and offline tools

In-person interactions can be crucial for digital social accountability initiatives. Here we explore what happens if it’s not safe to interact in person. The use of tech can contribute to the exclusion of vulnerable groups, so should we be rethinking our approach? And if we’re taking much of our work online, how can we ensure that those already at risk of exclusion are not further marginalised and excluded from this digital revolution?

The 2020 pandemic is clearly encouraging (or forcing) vast swathes of civil society to shift operations online. In-person interactions can be crucial for digital social accountability initiatives to work because demanding accountability operates through relationship building, trust building and negotiation which are easier face-to-face.

But what if it’s not safe to interact in person? We also know that the use of tech can contribute to the exclusion of vulnerable groups, so should we be rethinking our approach?

The question is, if we’re taking much of our work online, how can we ensure that those already at risk of exclusion are not further marginalised and excluded from this digital revolution?

This was the question I asked at the recent Dynamic Accountability Community of Practice Digital Dilemma event. I wanted to share a few practical insights that were discussed and examples of what Integrity Action is doing as inspiration for others who want to make their tech-based social accountability efforts more inclusive.*

Online and offline efforts work together

At Integrity Action, our tech tool DevelopmentCheck is used by citizen monitors to report on how well duty bearers are delivering what they have promised; from how schools are being run to whether contractors are using the right materials for construction of public buildings or water pumps. The tool shows any problems that have been identified within a service or project, as well as whether this problem has been fixed.

But the tool alone doesn’t get the problems fixed - this requires a broader approach including face-to-face engagement by the citizen monitors with duty bearers to convince them of why they should address the issues flagged. This can be quite a lengthy process involving several different tactics and stages, and can require experimenting with different approaches until a favourable outcome is reached. This is where offline engagement can really support the use of the digital tool.

Different ways to reduce exclusion

Although DevCheck is a tech tool, the way the tool works alongside offline engagement allows us to ensure that people at risk of exclusion are meaningfully involved as well. For instance, citizen monitors work in pairs so that a person who would find it difficult to use the app due to low literacy, or a visual impairment, can work with another person who is able to use the app. A monitor who might find it difficult to engage with the stakeholders responsible for getting problems fixed, perhaps because they have a hearing impairment, can work with a monitor who is able to engage directly and interpret the conversation.

We also aim to mitigate other types of exclusion such as ensuring that meetings and trainings are held in physically accessible locations, at an appropriate time for people who have child care responsibilities, and also allowing parents to bring infants they cannot leave at home along to the training. In addition, our approach ensures that projects specifically designed to support people at risk of exclusion are monitored, such as a school for deaf children in Kenya.

Smartphones for all?

But the simple fact that monitoring happens on a smartphone can make it inaccessible for different reasons. The people in our programmes who might not have experience with tech can be trained, but what about the prohibitive cost of a smartphone? We provide smartphones or tablets as part of our programmes. But we realise this is a challenge for sustainability, and are carrying out research into sustaining systems for citizen-led accountability. Get in touch if you’d like to hear more about that!

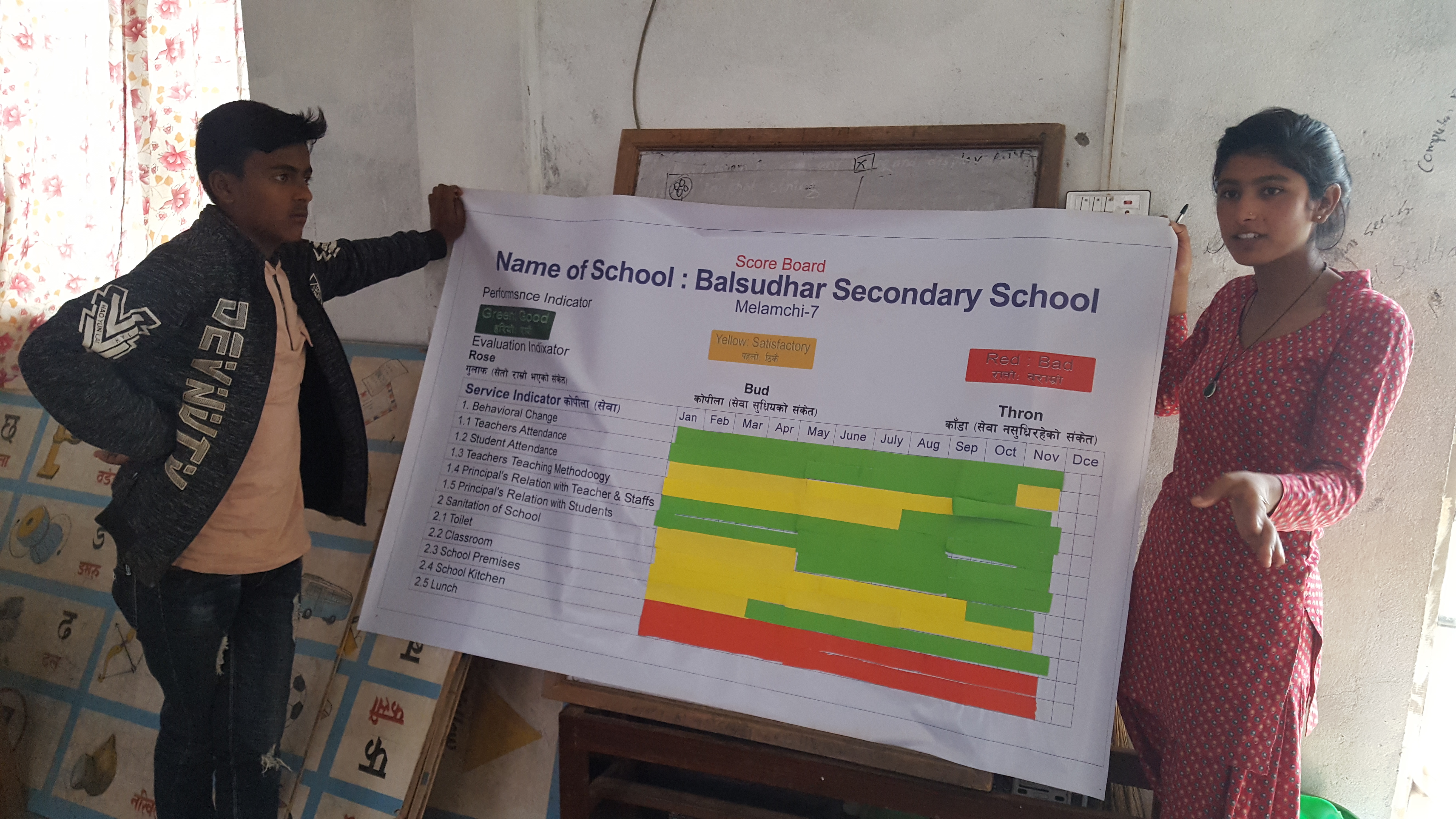

We are also looking to make our approach work when the technology cannot be used as intended. In Nepal where student monitors are not allowed smartphones at school, students collect data on how well their school is being run on paper, and this is entered into the app by support staff. A scorecard displayed in the school helps show students and staff how well the school is doing.

Be flexible

We also consider context specificity; what works in a school in Afghanistan might not work when engaging with local government officials in DR Congo. So another key facet of our approach is flexibility and adaptability - looking at the local context, testing different ways of working to see what achieves results, and aiming to facilitate cross-organisational learning so that our partners in different countries can see how communities elsewhere are doing it and get ideas for what might work for them. This is one area we are strengthening through our current focus on improving our monitoring, evaluation and learning.

To summarise, the fact that our tool is digital is an important part of why and how it works, but there is definitely a need for online and offline to be combined and neither is more valuable than the other. And by integrating the two, we find ways for also improving social inclusion.

This article was also published on the Global Standard for CSO Accountability blog.

*Please note that some of our work has paused due to COVID-19, and some is continuing where we’ve carefully considered the risks and implications and worked with our partners and the communities involved to adapt the programme accordingly.